International Women’s Day: How men in sports media can be better allies to women

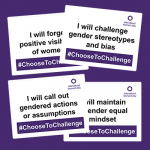

The IWD theme for 2021 is ‘Choose to Challenge’ – and for myself and my fellow men, the onus is very much on us if we’re serious about tackling gender inequality in our industry…

A timely email drops from Danielle Warby, the writer and women’s sport advocate, on the theme for International Women’s Day 2021 – ‘Choose to Challenge’.

“This theme only works for me if we’re asking men what they’re ‘choosing to challenge’ about gender inequality this International Women’s Day (and every day).”

I’ve challenged myself to write a blog for IWD about supporting women in sports media. Initially, I did ask myself whether I should – is that really what’s needed, to hear from another man?

Thanks to Danielle, I have context and direction. If through a blog I can help to reach more men in our industry and get them challenging the ongoing inequality and discrimination affecting women that surrounds us all daily – but which men often fail to acknowledge – that would be worthwhile.

Already I’ve made myself a little uncomfortable, which is exactly how I should be feeling.

For our community of LGBT+ people and allies in sport, we head into IWD off the back of a busy February for LGBT+ History Month and the Football v Homophobia campaign’s annual Month of Action. Both brought a wealth of outstanding content (and a special shout-out goes to all involved in the output from BBC Sport). It appeared to me that women were well represented – although there may have been gaps that I didn’t spot. Please let me know if so.

With that in mind, I was keen to pull out some examples from recent articles, podcasts, panel discussions, social media, etc, where women sports journalists and others working in roles related to sports media discuss their experiences and in doing so, help to provide men like me with some actions we can take that will help to challenge the status quo.

What is that, exactly? Here’s a snapshot…

- “Outside the period of major sporting festivals, statistics claim that 40% of all sports participants are women, yet women’s sports receive only around 4% of all sports media coverage” (UNESCO Gender Equality in Sports Media, 2018)

- “Less than 14% of sports journalists [in the USA] are female” (‘The GIST’s Ellen Hyslop Explains How Her Sports Media Startup Is Attacking Unconscious Bias’, Forbes, Feb 2021); the latest UK research on this is from around 2016, when the estimate was around 10% (BBC Academy)

- ‘Two thirds of Britons support equal media coverage of men’s and women’s sports, but for many that is conditional on there being no decrease in coverage of men’s sports’ (YouGov survey, 2020)

- “Nearly one-third of female journalists consider leaving the profession because of online attacks and threats” (International Women’s Media Foundation, 2014)

There are other pertinent stats available but what’s also apparent is the relative lack of up-to-date data that points to the representation of women in specific roles in sports media, particularly in the UK, and how that correlates to coverage, perceptions of the industry, and retention of staff.

It’ll take a combination of stronger leadership and energy from editors and directors; better recruitment practices; a greater appetite for consumption of women’s sport from the public; and safer spaces on social media to shift the above numbers in the right direction. Again, it’s men who hold the power here, and only when we ‘choose to challenge’ will significant movement occur.

The foundation to that is the kind of daily allyship that brings tangible change to newsrooms and sends messages up the chain that are acted upon decisively. Creating inclusive cultures has long-term benefits – when people embedded in those cultures move into positions of influence, they appreciate the need to ‘hold the ladder’ for others to climb.

Here are five suggestions of ways men can be better allies to their colleagues and peers in sports media who are women. As we’re an LGBT+ and allies group, I’ll also attempt to consider actions that support LGBT+ women and non-binary people who face gender inequality...

Accept you will make mistakes – learn from them so you can ask educated questions.

This seems the best place to start. Knowledge gaps, a lack of appreciation, failure to empathise, ‘mansplaining’… we all slip up. But how do we react? Good responses would be recognising where we fall short, brushing up on our understanding, putting ourselves in the shoes of others, and most important of all, listening.

There is ample scope for education. It’s only in recent years that topics such as period pain and the drawbacks of women’s kit and gear have received mainstream sports media coverage and for myself and – I hope – many other men, reading these articles and others was eye-opening.

Another learning opportunity – Olympic gold medal-winning cross-country skier Jessie Diggins recently wrote for NBC On Her Turf and on her own website about how a line of questioning from a male reporter about weight and body size after an event demonstrated perfectly why there’s a need for greater representation of women in sports media.

When men are more informed and can discuss the subtleties beneath the surface of women’s sport, our colleagues who are more familiar with these topics than us won’t feel they have to use their time to take us back to school. They can move ahead more swiftly with their reporting.

Telegraph Women’s Sport and GiveMeSportW are two dedicated UK publications that men should be reading regularly; across the pond, there’s ESPNW and the Burn It All Down podcast, while new media venture Togethxr has just been launched. You can also subscribe to these excellent email newsletters…

- Danielle Warby

- Siren Sport (Australia)

- Power Plays, by Lindsay Gibbs (USA)

- The Gist (USA)

Another encouraging sign comes from the Park School of Communications at Ithaca College in New York State. The School has introduced a new Women’s Sports Media incubator course this semester, with Professor Ellen Staurowsky telling The Ithacan “we needed to be graduating our students with a much more nuanced appreciation”.

Of the 25 students currently enrolled on the course, 14 are women. Sophomore Jake Lentz said: “We as a department can change the way we can get more women involved in sports media. For men, it gives them things to look for that they do without thinking that could be disrespectful towards women in the field. For women, it gives them a safer environment to talk about things.”

It’s a refreshing approach that’s reflective of the changing times – and demonstrates a commitment that others in education would do well to emulate.

Help with visibility and amplifying voices

This may seem an obvious way to be an ally, but it requires some additional thought.

We all have access to social media accounts (even if it’s just for personal use); some may operate websites or blogs; a few will also have access to big media platforms, and get to make the kind of editorial decisions that seriously increase the number of eyeballs on both women’s sport and the work of women journalists. Then there are other opportunities – whether you’re involved in a podcast, a YouTube channel, planning panel events, etc – where men can suggest swinging the spotlight across or turning up the volume to get more women seen and heard.

While these are undoubtedly effective methods, it’s also vital to appreciate the effects of visibility and amplification. Often it can bring extra pressure, responsibility, and – inevitably – criticism, in the most part from men. It’s not a case of having to develop a ‘thick skin’ to cope because criticism directed at women journalists is often personal, and in no way constructive.

Last month, The Athletic’s women’s football correspondent Katie Whyatt wrote a thread on Twitter about some of the trolling she has experienced on social media and that, while the specific platforms need to do more to tackle online hate, she feels the abuse is an extension of both “real life” and the patriarchal football culture in which men and boys are often “intolerant of women sharing any space”.

Making women sports journalists more visible won’t offer them many positives if men fail to assist when they are targeted or shouted down by other men. If we’re really going to champion our colleagues, we need to demonstrate why we value their output highly, endorse their work more frequently elsewhere, and consciously make room for them in parts of sports media where they are represented less often. That will benefit both coverage and culture, and grow reputations on merit.

For women who are LGBT+ striving to get ahead in sports media, there may be additional concerns around visibility. On the LGBT+ History Month episode of The F in Football Podcast, hosts Amelia and Emmy discussed a point made by Anita Asante from the FA’s Pride Month discussion last year…

[Women’s football] has always been considered more inclusive but with the visibility and interest that comes from commercial sponsorship, TV and media, you see that some girls are more self-aware about their image, personality and persona and the limitations that come with that because of negative stereotyping related to LGBTQ+.

Anita Asante

On the podcast, Amelia reflected on Asante’s point: “She’s saying that because the women’s game is becoming more popular, it might have a negative effect on some of the players’ self-confidence with their sexuality… they might think it’ll have a negative impact on their future career – for example, when they finish football and if they wanted to go into media… I’d never thought of that.”

If there is any perception that women who are not LGBT+ are being favoured in terms of opportunities in sports media, that’s not going to encourage anyone in the community to be out. Visibility isn’t effective if a certain image or ‘look’ is being prioritised, particularly when you consider international broadcasting and parts of the world where anti-LGBT+ laws and attitudes persist.

Men largely hold the power of which women get to be visible in sports media. Talent should be the deciding factor but we’d be naive to think that’s always the case.

Encourage authenticity and personality

Another Athletic employee, deputy editor Laura Williamson, was asked by Durham’s student newspaper The Palatinate what makes young journalists stand out: ‘[Williamson] is largely unequivocal: personality. She mentions traits such as ambition and drive, and the ability to make her think “readers are going to love you”.’

Sports Media LGBT+ has its own initiative called #AuthenticMe, so it should come as no surprise that Laura’s view resonates strongly with me. On the aforementioned podcasts and panel chats from recent weeks, several women sports journalists have spoken about how embracing their sense of self and identity has been integral to their career progression. Here are some examples that describe this and hint at male allyship…

Beth Fisher, Sam Adams’ It Starts With You podcast

“I either do things fully or don’t. I’m really lucky I’ve got this job with ITV Wales. When I went for the interview, I’d never done any TV work… and had never worked full-time in media. Typical female, I wasn’t going to go for it. But I was told I should, I went, and I was my complete authentic self in the interview – I thought if they don’t want me as who I am, then I don’t want to work here. I was lucky there was a diverse interview panel – a gay man and two females.”

Dawn Ennis, FARE v Homophobia panel discussion

“I had to hide who I was and to pretend to be this person who everyone saw as a man for almost 40 years of my life – I knew since age four – but when I finally was able to be myself, I was amazed by how most people who I work with said, ‘I see it now, I get it..’ It wasn’t just the outfit or my hair changing or anything, it was about how I lived my truth, and how I was carrying myself, and being a better journalist because I was not worried about having to pretend anymore.”

Emma Smith, Diversity in Football media panel discussion

“I was out of work and it felt like it would be almost impossible to try and get into it as a transgender journalist because there didn’t seem to be any other trans journalists in sports journalism. It didn’t seem like it would be a place for me but I had to keep applying… Goal wasn’t the first place I had an interview but it was the first place where as soon as I walked in, it felt like I wasn’t going to be treated differently and that it would be based on my abilities as a journalist. And that’s always how I’ve felt while I’ve been at Goal.”

It’s reassuring to hear these experiences from a male-dominated industry, but they are not universal. Saying ‘be yourself’ to women in sports journalism is very easy but again, it puts pressure on the individual when you consider that it’s mostly men who control the newsroom environments and also consume the content produced by those newsrooms. If you feel that to succeed and be respected, you have to fit in, how can you ever stand out from the crowd? Izzy Westbury described this well on Sky Sports’ The Cricket Show…

The problem is that women are trying so hard to conform to this ideal of being the perfect broadcaster that you lose the personality.

Izzy Westbury

A good ally should challenge the notion of what ‘perfection’ looks like – it’s almost always a male gaze interpretation that doesn’t offer much capacity for character – so that women can bring both their personality and their passion for sport to their roles.

In her recent podcast interview, Beth explains how her use of social media reflects her campaigning streak and how that underpins her commitment to journalism…

I am opinionated but everything I tweet, even if it’s strong, the basic value is fighting for people to have human rights. It’s accessibility… I’ve always got in the back of my mind that it [the tweet] will be there forever. I’m on a few people’s ‘delete list’, but I’m not here to make friends, I’m here to make change.

Beth Fisher

Women are constantly challenging the traditions and structures of sports media. Men need to support them in doing that or – to borrow a phrase from Burn It All Down – pick up a flamethrower themselves and join in.

Use your privilege to call out inequality and discrimination

“Hey! That’s not OK.”

Uttering this phrase in a situation where someone has shown bias, stupidity, or worse towards a woman means recognising that you have an advantage due to being in a place of privilege; and finding your voice when you could choose not to.

Privilege in sports media is everything that we don’t have to deal with to do our jobs. Sexism and misogyny; tired old stereotypes about being a lesbian in sport; microaggressions; misconceptions about being trans, more obvious elements of transphobia; to name but a few. Ask yourself if, as a man, you would be treated in the same way in a given situation. If we can’t empathise with our colleagues and respond accordingly (speaking up is the least we can do), we’re never going to be effective allies.

It’s also about the occasions when ‘performative allyship’ isn’t even an option – these require more effort. In a blog for Deadspin, Julie DiCaro – the author of ‘Sidelined: Sports, Culture, and Being A Woman in America’ – writes: “We need men to take it upon themselves to report other men, to call out bad behavior when they see it, even if there are no women around. We need them to decide they won’t wait for women to report sexual harassment, they’ll do it on their own.”

I’ve mentioned online trolling and much of that is directed at women sports journalists when they ‘dare’ to cover men’s sport. Freelance sports journalist and broadcaster Florence Lloyd-Hughes, who regularly reports and comments on QPR’s men’s team, talks about her experiences on a recent episode of Rebecca Roberts and Harriet Small’s ‘Have You Got 5 Minutes?’ podcast, explaining how she made a report to the police and repeatedly set her profiles to private after an onslaught of abuse.

We all know social media platforms aren’t doing enough to combat online hate but the least men can do is report these posts when we see them, and send a message of solidarity to the person on the receiving end of the abuse, in a way that doesn’t exacerbate matters. Sadly, the hate also manifests itself in direct messages which aren’t visible to others – if you see that a woman sports journalist has locked their account, that’s a sign. Consider how you can best offer meaningful support.

Gender inequality can present itself in many other ways. The demanding nature of a career as a sports journalist, with its unsociable hours, takes its toll on family life. The privilege of time is a rare and valuable commodity in the media industry – if you can spare any, try using it to take some pressure off a colleague who is finding it hard to juggle her commitments.

As men, we can also set good examples with our use of language and terminology. Not using gendered words like ‘guys’ when addressing a group of colleagues in the workplace; adding your pronouns to your email signature; double-checking words that act as ‘labels’ in content with the individuals being referred to… part of using male privilege effectively is making life more comfortable and welcoming for those who are less privileged. Ensuring we have an inclusive vocabulary asks little of us but means a lot to others.

Trust women journalists to know their patch

We’ve established that there is a shocking lack of both women sports journalists and women’s sports coverage. By no means should it be the responsibility of the former to fix the latter. With that said, expertise counts for so much, and when harnessed effectively, all women benefit.

The Athletic recently ran an excerpt from the book ‘Loving Sports When They Don’t Love You Back: Dilemmas of the Modern Fan’, by Jessica Luther and Kavitha Davidson…

“Even if reporters, editors, writers, and broadcasters from underrepresented groups don’t want to only be known by a certain identity, until the industry fixes its diversity issues they are going to be called on to help their more privileged peers navigate issues of sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, and other issues.”

Men can empower women to report on specialist areas of sport without ‘pigeon-holing’ them – just don’t ask those same women to do all the heavy lifting. I can relate a little – I feel empowered to write about being LGBT+ in sport for my employer Sky Sports because I’ve seen a wider commitment to inclusion that goes beyond just my own contribution. Therefore, part of the ‘challenge’ for all men on IWD 2021 in our industry is to do things differently – don’t go with the flow, look for stories that are rarely told (women’s sport is full of them), and then look for the people best placed to tell those stories.

Trust goes beyond just commissioning a story and rewarding the labour involved. Make yourself available throughout the process so you can talk through ideas, assist with contacts, open doors for imagery and design, etc.

At Goal, Emma Smith has been able to bring several stories about the LGBT+ community in football to the platform that would otherwise not have been covered. She explained in the FvH panel discussion on diversity and inclusion in media…

“Most of the senior staff are white male journalists but they trust you – you can see that in the way I’ve written about being LGBT+ in football. That’s been fantastic. I feel like I can pitch interviews on these topics and I’ll get the necessary support in terms of being prominent on the website.”

Prominence is significant – it would be easy for an editor to allow this work to be done and then sit back and allow it to be buried on a website.

It’s not just about content, either. On Sue Anstiss’ Game Changers podcast, Jess Creighton speaks of the need to have an intersectional approach to all aspects of challenging the sports media…

“Yes, I am black but it’s not just racial diversity that I want to change. In terms of the LGBTQ community, figures within the media industry are shockingly low. Gender is terrible – 25% of newspaper front pages are written by women. Not good enough. Just 0.4% of the media industry is Muslim – not good enough. There’s a lot I want to change that isn’t just about race.”

One example of how Jess did this herself was by bringing a suggestion to the organisers of the Football Black List that they should introduce an annual LGBTQ+ award. Through her own experience of inhabiting multiple identities, she knew the impact that this award could have but it required the FBL to trust in her vision. There was some apprehension on her part…

“That’s how it seems sometimes when you challenge authority and leadership within the media industry. They get defensive and they don’t want to hear from someone lower down from them… but with the Football Black List, it wasn’t like that at all… it was a brilliant example of leadership… I was so proud of the FBL that day, and of my community.”

It’s going to take a long time for the British sports media to be truly reflective of diversity. Until then, editors should maximise the potential of the diverse talents within their newsrooms by recognising and celebrating them. Emma can see that attitude acted upon at Goal, adding: “That’s what being an ally is – trust your LGBT journalists to do their journalism properly.”

Thank you to the women quoted in this article, and all in our sports media industry who are striving to make every day International Women’s Day.

Recommended reading…

How to Be an Ally in the Newsroom (Source by OpenNews)

Being an Effective Ally to Women and Non Binary People (Code As Craft)

Sports Media LGBT+ is a network, advocacy, and consultancy group that is helping to build a community of LGBT+ people and allies in sport. We’re also a digital publisher. Learn more about us here.

LGBT+ in sports? Your story could help to inspire other people – you don’t have to be famous to make an impact, and there are huge gains to be made both personally and more widely in sport. Start a conversation with us, in confidence, and we’ll give you the best advice on navigating this part of your journey.

Email jon@sportsmedialgbt.com or send a message anonymously on our Curious Cat.